Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 is a high-quality standard lens, released in 1966, along with the Mamiya 500TL camera and is recommended by vintage lens lovers as one of the best. This lens was one of the first vintage lenses in my collection and kick-started my journey of discovery.

Everything would be fine if we just stopped here. However, interest is fueled by appreciation, and we strive to dig deeper, only to discover that this lens exposes the bottomless rabbit hole. We still have many unanswered questions. Who made it? Who designed it, and how? Mamiya, Tomioka or maybe Carl Zeiss?

Build and handling

Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 is a solid lens made from quality metal parts and rare-earth glass. Nothing rattles inside when shaken, and everything feels tightly aligned and well-engineered.

Focussing is smooth, as one would expect from the brass helicoid. The aperture selection ring rotates smoothly with tactile clicks, allowing the setting of the half-stop apertures.

I love vintage lenses precisely for the above points – modern lenses lack these qualities, even the expensive ones.

Optical performance

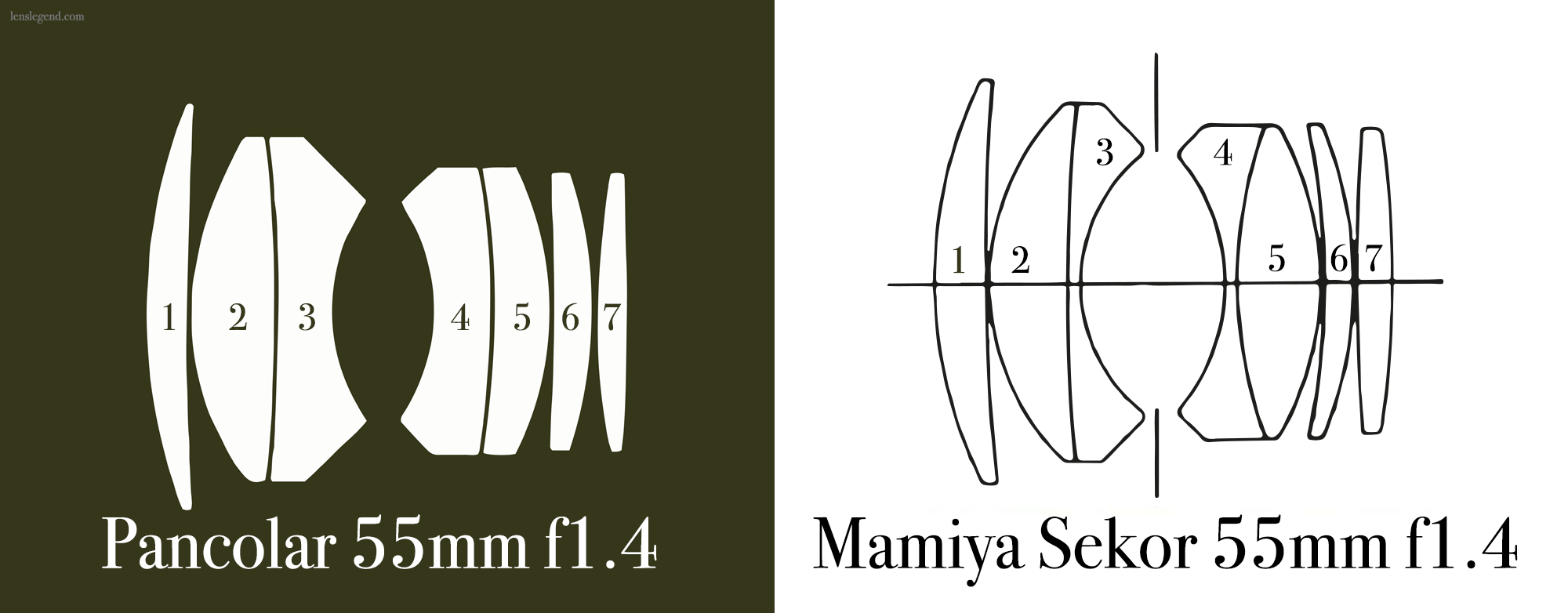

Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 features an optical design associated with the finest lenses in the vintage lens world, costing many times more than its price. People compare its rendering to the Carl Zeiss Contarex 55mm f1.4 and Carl Zeiss Jena Pancolar 55mm f1.4 – both excellent lenses, unfortunately, both way above my price range. I understand that there is an element of wishful thinking there, but these comparisons would not happen without merit, and the Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 deserves the honour.

To some vintage lens enthusiasts, this is the one lens to rule them all. It has buckets of character (meaning flares, ghosts and spherical aberrations). Still, in the hands of the accustomed user, it can produce spectacular sharp, warm images with an authentic vintage feel.

Spherical aberration is strong when wide open at f1.4 – not a strong negative point. A creative photographer can use it for portraits or any other dreamy-looking photos. However, when stopped down – it is very sharp and resolves a lot of detail. This ‘soft when needed’ and ‘sharp when needed’ combination is a win, in my opinion. Just make sure you set the aperture accordingly.

Radioactive thorium in the lens elements gives this lens a “thorium glow” because the thoriated glass yellows with age, acting like a mild yellow filter. Although it is possible to clear it away by exposing the lens to UV light, I prefer the warm look.

Overall, I like the look of the photos it produces – those images pack the visual qualities and quirks I value.

Versions

This lens has many subversions with different rear elements and radiation profiles indicating differing glass. Early Mamiya Sekors had the “MAMIYA – SEKOR” label, while later ones were labelled “MAMIYA / SEKOR”.

Radioactivity

All three of my Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4s are radioactive. However, the radiation strength differs between the models – I measured the surfaces with my sensitive GQ GMC-600+ Geiger counter, which detects alpha, beta, and gamma radiation. I find radioactive lenses immensely appealing because they use unique optical glass formulas no longer in use today. To learn more, read my extensive article about radioactive lenses.

Mamiya – Sekor 55mm f1.4 – No. 13850

Front element: 185 CPM / 0.52 µSv/h, Back element: 18335 CPM / 52.5 µSv/h

Mamiya / Sekor 55mm f1.4 – No. 94698

Front element: 2619 CPM / 7.5 µSv/h, Back element: 668 CPM / 1.9 µSv/h

Mamiya / Sekor 55mm f1.4 – No. 100626

Front element: 2629 CPM / 7.7 µSv/h, Back element: 16900 CPM / 56,0 µSv/h

Cosina Cosinon 55mm f1.4 – No. 712102

Non-radioactive

Rolleinar-MC 55mm f1.4 – No. 7107745

Non-radioactive

Similar lenses

Cosina Cosinon 55mm f1.4

Tomioka Auto Revuenon 55mm f1.4

Tomioka Auto Rikenon 55mm f1.4

Tomioka Auto Chinon 55mm f1.4

Rolleinar AR 55mm f1.4

Voigtländer Color-Ultron AR 55mm 1.4

Sears 55mm f1.4

Pros and Cons

Pros:

Unique and mysterious lens design

Sharp and contrasty from f2

Built well using premium metals and glass

Moderately priced

Cons:

Spherical aberration at f1.4

Specifications

Focal length: 55mm

Aperture: f1.4-f16

Aperture blades: 6

Construction: 7 elements in 5 groups

Mount: M42

Focus: Manual

Radioactive: Yes

Year released: 1966

Made in: Japan

History and questionable origins

Mamiya bought the ‘Setagaya Koki’ factory in 1946, which manufactured lenses and shutters for Mamiya – that is what gives the “Sekor” its name. After various merges and changes, Setagaya Koki was closed in 1964 and relocated to Urawa, where the new Mamiya factory was established. At that time, Mamiya started outsourcing lens production to other manufacturers, and it became challenging to pinpoint who made the lenses.

Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 similarity to Pancolar 55mm f1.4

I read a claim on one popular photography website that Mamiya Sekor 55mm is ‘certainly’ based on the Carl Zeiss Jena Pancolar 55mm f1.4. There are indeed noteworthy similarities between the lenses – both ‘Pancolar’ and ‘Sekor’ are radioactive, contain thoriated glass, and have seven elements in five groups. Both have the matching position of cemented groups (1-2 | 2-1-1); however, the shapes of the cemented elements are different, with the most significant difference evident in elements 4 and 5. Likewise, this claim is not justifiable in the timeline of events – Mamiya released Sekor 55mm f1.4 in 1966, while Carl Zeiss Jena released Pancolar 55mm f1.4 only in 1967.

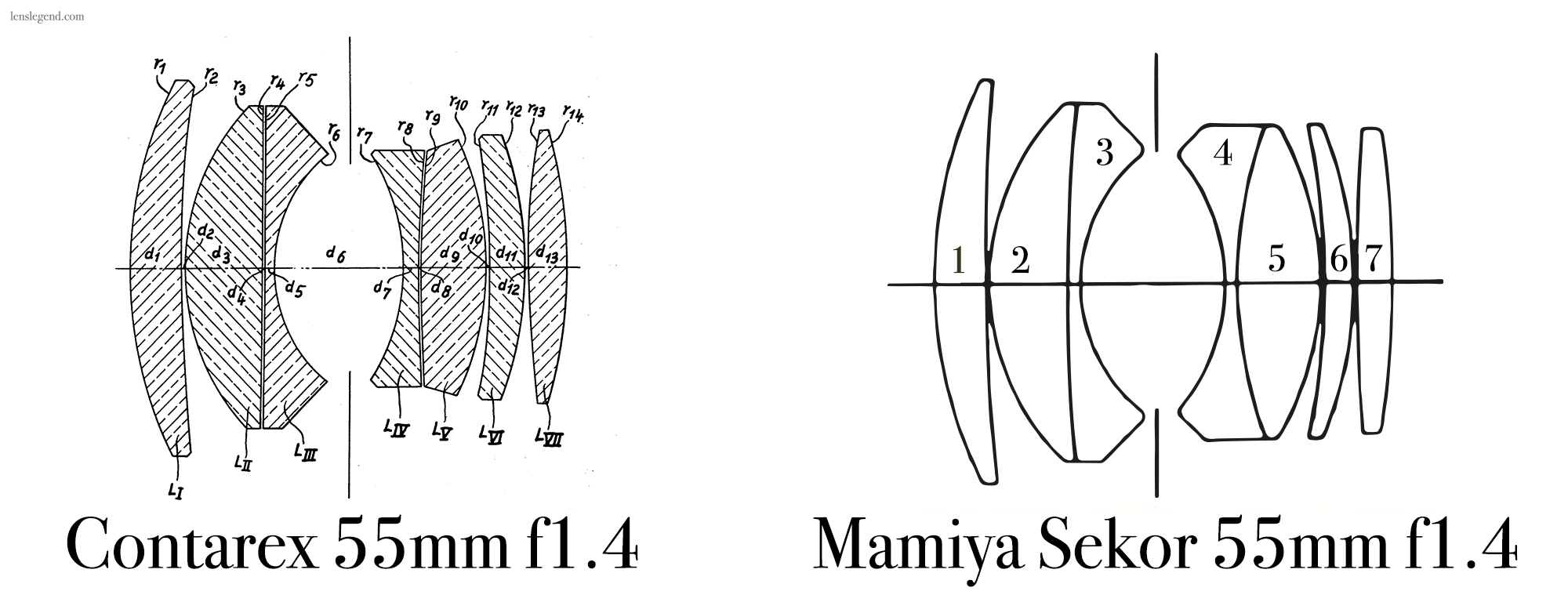

Mamiya Sekor f1.4 similarity to Contarex 55mm f1.4

Various vintage lens forum members also claim that Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 is based on the Contarex 55mm f1.4. Both lenses have seven elements in five groups, and the main differences are only in the curvature of the elements in the cemented groups. However, Contarex was not radioactive, unlike the early versions of the Sekor, which are radioactive – indicating considerably different glass formulas. Contarex was released in 1961 – a few years earlier than the Sekor, in theory, giving time to base the Sekor on the Contarex.

Carl Zeiss only created a successor to the Contarex lens in 1972, so it seems unlikely that Carl Zeiss would view its design as insignificant and licence their current top-of-the-range lens to Japanese manufacturers in 1964. The Japanese might have used the invention without permission, but it seems unlikely, given the number of similar designs already patented in Japan at the time.

55mm f1.4 – an organic Japanese design?

It is a Western-centric misconception to look at the Japanese lenses as inferior to the Western ones. This view backs the idea that the Japanese “must have copied” the Contarex or the Pancolar. However, what if the 55mm f1.4 was a homegrown Japanese design? Japanese engineers had the technology, know-how, and prior patents to make it happen.

In 1970, Leitz sent two of its top engineers to Japan to investigate the technological level of the Japanese optical industry when the aforementioned Leitz and Minolta formed the alliance. In the survey, Leitz reached the conclusion that Japan’s technological level is the same as that of Leitz, the lens performance is top-notch, especially in terms of small aperture and telephoto, and the single-lens reflex camera and mass production system are outstanding. (“The Story of Leica: The Secret of Leica No One Knows” p.209). On the other side of the alliance, Minolta, among the older engineers, there were those who favored the alliance, believing that they should repay the kindness even if Minolta had to take the lenses out of the company. , the young technician was reportedly cold. Mr. Toshifu Ogura, the lens designer of Minolta, said that there are many lenses that Leitz wants, but there are few lenses that Minolta wants. (Soshisha “Aiming for Leica! Trajectory of Japanese Cameras Followed by a Technician” p.255-262, Soshisha Bunko edition p.293-301). –Machine translation from Asthenosphere Blog

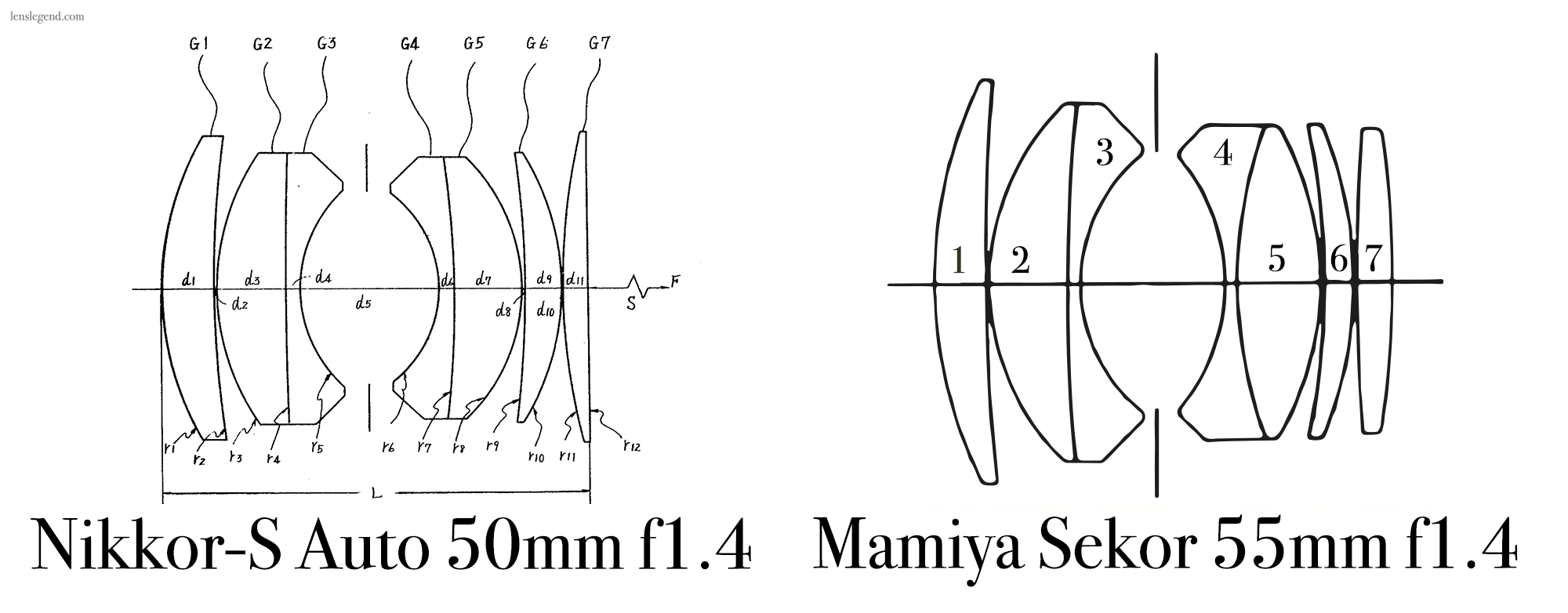

In 1962 Zenji Wakimoto and Yoshiyuki Shimizu of Nippon Kogaku Co., Ltd. applied for Japanese Examined Patent Publication 40-386, which contained a lens schema for Nikkor-S Auto 50mm f/1.4, which was similar to the Mamiya 55mm f1.4 and had a flat rear element. However, the cemented group containing elements 4 & 5 had different curvatures.

The slight difference in design supports the hypothesis that the designers of the Mamiya 55mm f1.4 could have based their lens on something existing locally and licensed it or tweaked the formula to go around the patent. Many Japanese camera makers were then collaborating, so licensing seems more likely.

Anti-copying arguments

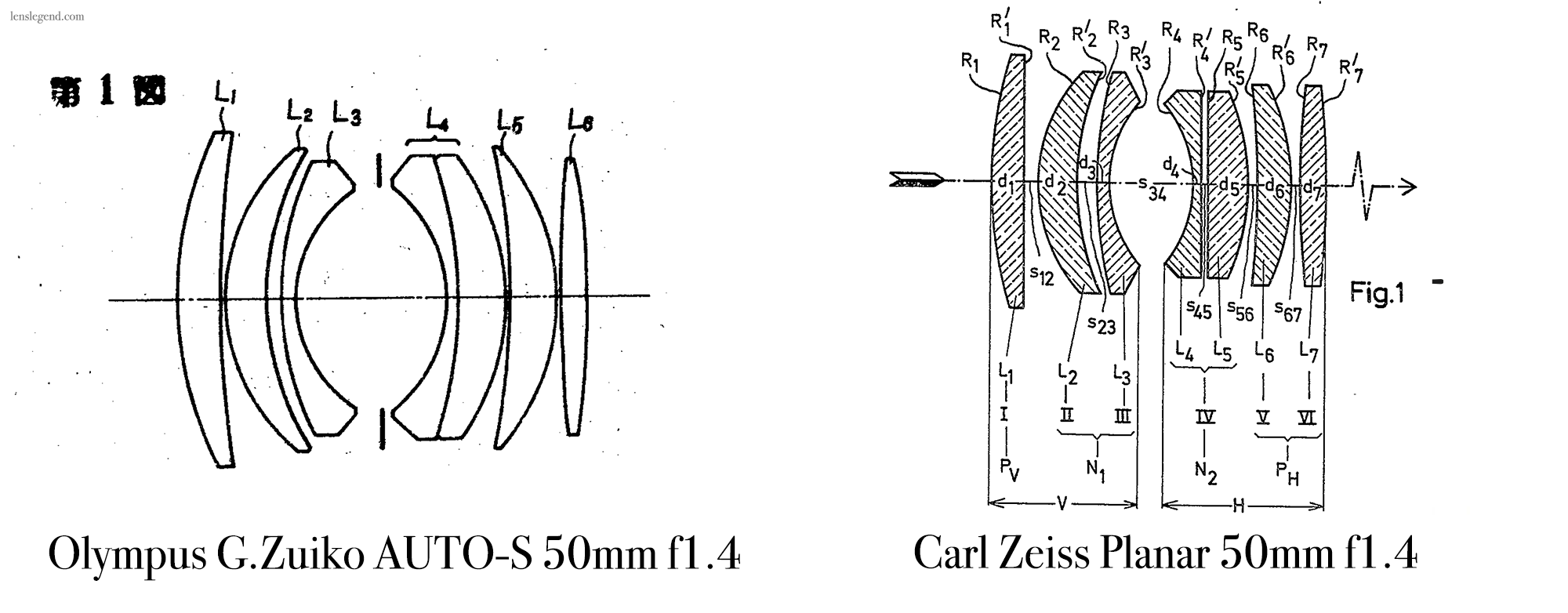

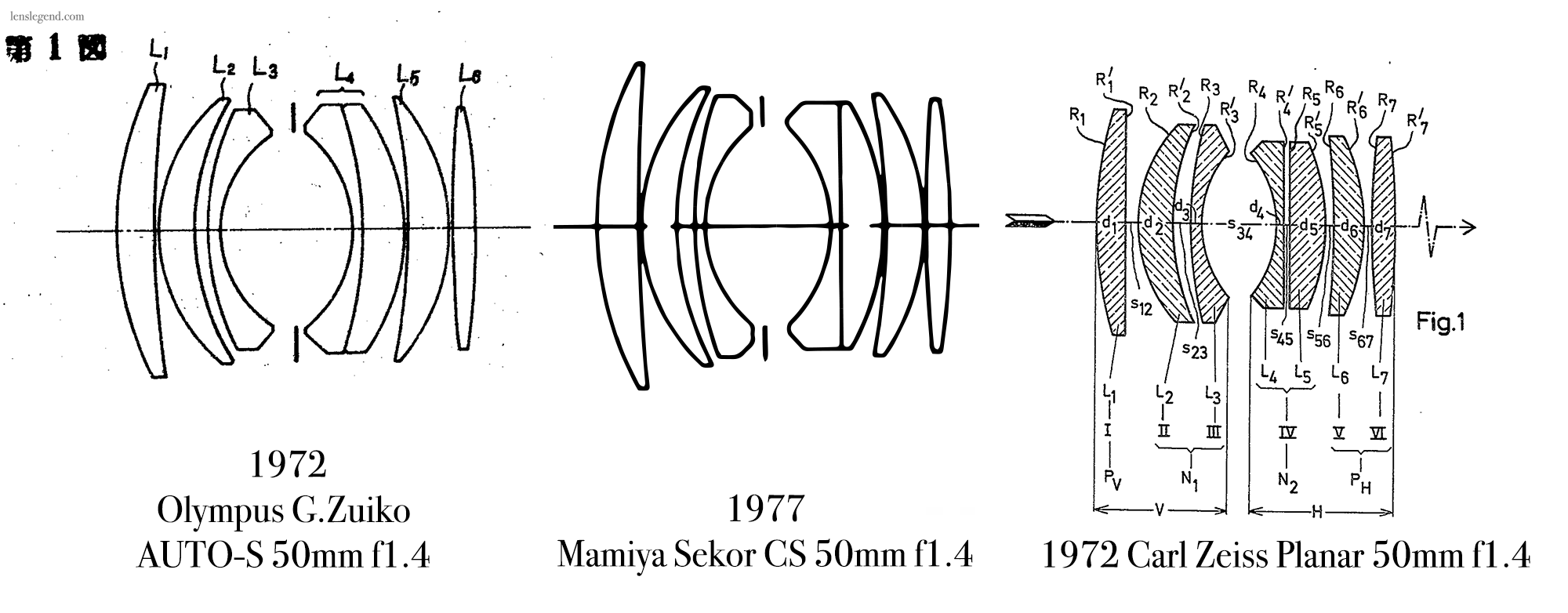

Olympus filed the patent Publication No. 50-35813 for the G.ZUIKO AUTO-S 50mm F1.4 on May 4, 1972, and on November 19, 1975, it was granted as Japanese Patent No. 821334.

In 1973 Carl Zeiss applied for a Japanese patent for the new Planar 50mm f1.4 but encountered problems. Japanese manufacturers already had similar designs with prior patents, and the Carl Zeiss patent met resistance from the Japanese Patent Office.

In fact, on April 4, 1978, the Japanese Patent Office rejected Zeiss’ Japanese Patent Application Showa 48-73540 as not worthy of a patent. After that, Zeiss filed an appeal against the decision of refusal, repeatedly submitted notices of reasons for refusal and written amendments, and finally reached a public announcement decision in 1983. The issue was registered on September 26, 1984. – Machine translation from Asthenosphere Blog

The author provided no references to verify the above information. Nonetheless, open databases confirm that the patent application was made in 1973 and only published in 1984 – a total of 11 years later, suggesting the above statement could be correct.

Looking at the above drawings of the Olympus patents, we could make a hypothetical counter-argument that the Japanese lenses could have influenced Zeiss and not the other way around. Likewise, it should give us sufficient confidence to say that Japanese and German manufacturers alike did not need to copy each other.

Another argument against unlawful copying is the production of the Rolleinar 55mm AR lens from 1977 until 1981. If Rollei or Zeiss knew that Mamiya unlawfully copied their designs, they would not have given Mamiya a contract to make the Rolleinar for Rollei – demonstrating that Mamiya, Rollei and Carl Zeiss were on good terms.

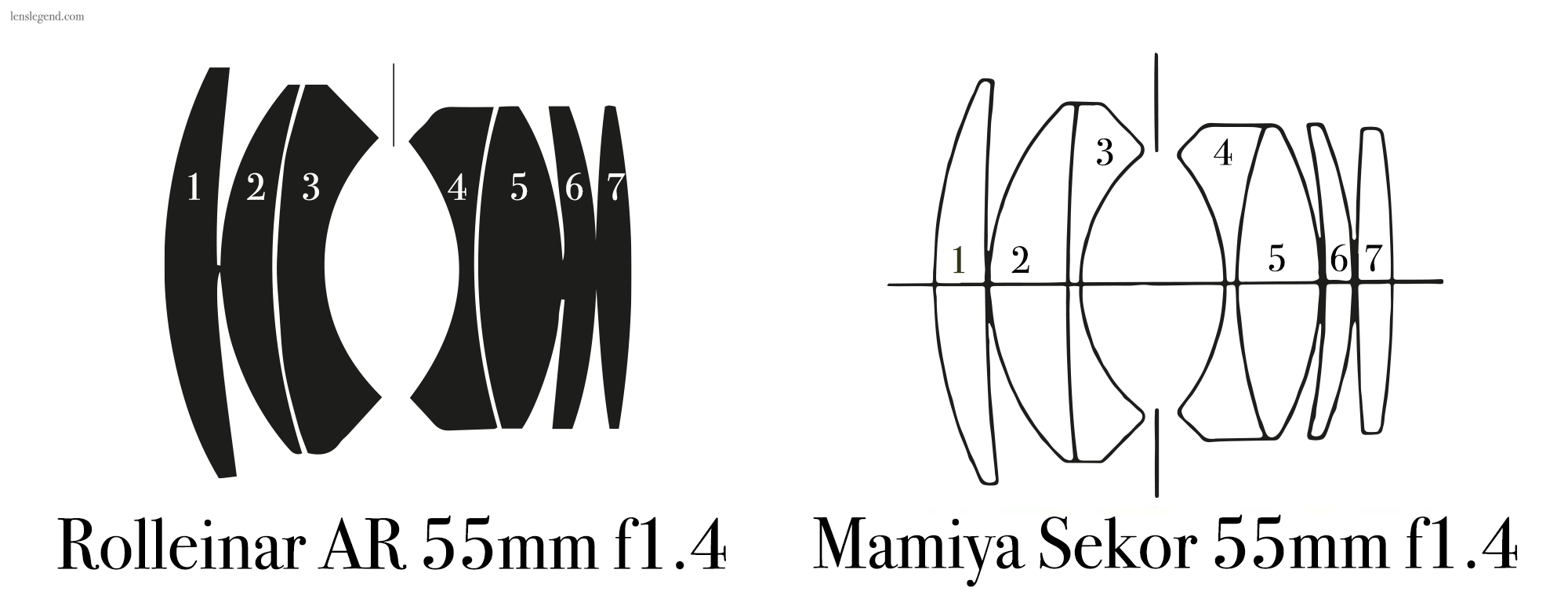

Rolleinar AR 55mm f1.4

Rolleinar AR 55mm f1.4 was a lens made by Mamiya for Rollei in Germany and released in 1975. Rollei was selling rebranded Mamiya lenses as Rolleinars to introduce cheaper lens options alongside expensive Carl Zeiss for its camera line.

The Rolleinar (Color-Ultron) 1:1.4/55 mm was built for Rollei from 1975, but was the license-free (expired) CONTAREX PLANAR , constructed in 1959 (Thi.S.91) – Patent DE1170157 v. Johannes Berger, Dr. Günther Lange – produced for Contarex from 1961. Zeiss did not extend this patent because in 1973 the Planar 1:1.4 / 50 mm for Contax and Rollei SL 35 was an absolute top lens. Rollei was able to have this lens manufactured as Rolleinar without paying a license. (Dr. A. Tronnier) – classic-cameras.de

Claims that Rolleinar 55mm f1.4 was based on the Contarex design generate more confusion. By 1975, the original Contarex patent had likely expired, which could have allowed Rollei to reuse the Contarex lens design and commission Mamiya to build it.

However, even if the optical designs were licenced by Mamiya or even adopted licence-free in 1975, it does not explain how Mamiya and Tomioka constructed a lens using this design back in 1966. The patent was in full force and relatively fresh, and Carl Zeiss would have protected it.

The diagrams of the 1966 Sekor and 1977 Rolleinar match visually, but there is a hidden difference – the 1966 Sekor is radioactive, utilising thoriated glass, while the 1977 Rolleinar is non-radioactive, indicating at least a recalculation and slight changes must have occurred.

General similarity to the 1966 Sekor means the differences to the Contarex (discussed in the Contarex section above) remain unchanged.

In the case of licensing, the design of Rolleinar would closely follow the Contarex, and we would see a significant difference to the old 1966 Sekor, but we see little of that.

Additionally, there is no proof or record of such an agreement, so it is unclear whether it happened or is that simply a feature of internet lore.

Drawing parallels with the Mamiya CS 50mm f1.4

Mamiya released Sekor CS 50mm f1.4 along with the NC1000 camera in 1977. It featured a new ‘seven elements in six groups’ design sharing many similarities with the Olympus 50mm f1.4 and the new Carl Zeiss Planar 50mm f1.4.

The pattern of ‘no known patent, but recent lens design’ continues. This practice could support the hypothesis that Mamiya was licensing other Japanese makers’ designs, explaining why there are no independent patents for either Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 or the Mamiya Sekor CS 50mm f1.4.

For a short time, Mamiya also bought lenses from Olympus Optical. – http://herron.50megs.com/history.htm

The above statement also hints at a Mamiya / Olympus relationship, which could have resulted in Mamiya licensing lens designs from Olympus or other Japanese makers, either earlier for the Sekor 55mm f1.4 or the CS Sekor 50mm 1.4. It is a wild speculation on my part, and I have not found any proof.

However, we also know Zeiss had difficulties patenting the Planar, possibly allowing Mamiya to use the design licence-free until 1984.

Most likely a coincidence, but Mamiya stopped making 35mm cameras in 1984, just as the Carl Zeiss Planar 50mm f1.4 patent was published in Japan. It is, of course, pure speculation.

Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 Tomioka connection

Tomioka undoubtedly made some early Mamiya Sekor lenses, but finding them takes work. The easiest way to identify a Tomioka is to read it on the lens name – for example, Revuenon Tomioka, Auto Rikenon Tomioka, and Auto Chinon Tomioka – all of which have 55mm f1.4 models. Unfortunately, no known Mamiya Tomioka co-branded lenses exist.

Tomioka also made lenses with no branding; on some models, the label only appeared later when Tomioka became a known brand. Opposite examples also exist – the first version of Auto Chinon Tomioka did have the brand but later changed to Auto Chinon, even though the lenses were identical.

We can look for the Tomioka-built lenses by comparing the features of the suspected Tomiokas to the known Tomiokas.

The flat rear element is one often debated feature. Tomioka and Cosina made 55mm f1.4 lenses for various brands – with both flat and convex rear lens elements. If it were a Tomioka signature to make lenses with flat rear lens elements, then why is the rear lens element of my Cosina Cosinon 55mm f1.4 also totally flat? It is not reliable to differentiate the manufacturer based on the shape of the rear lens element alone.

Determining Tomioka lenses

I wholeheartedly thank Hidehito Yamanaka for leaving an informative comment describing determining if a lens is a Tomioka and expanding the history of how Tomioka is tied with Carl Zeiss in West Germany. He has confirmed that all three of my pictured lenses are, in fact, a Tomioka build.

I work on completely disassembling and overhauling old lenses. I introduce the work scene on my blog, and I have found that the only way to determine whether a lens is made by Tomioka Optical is for the M42 mount.

There are several reasons for this, and they can be seen in the three lenses in the photos you posted on your site (all three are made by Tomioka Optical). The reason is the three screws used from the side just before the mount. Tomioka Optical was the only company that used this type of screw to tighten the frame from the side at the time.

Furthermore, only Tomioka Optical lenses had a special design that ensured consistency between the aperture value of the aperture ring and the click feeling. It uses a complex design that uses three points: the lens barrel, the aperture ring, and the mount, which was a more rational and efficient design than other Japanese optical manufacturers.

There is also evidence that it is definitely made by Tomioka Optical in the lens barrel that houses the optical glass lens. It is the “design concept that precisely controls the opening and closing angle of the aperture blades.”

Hidehito Yamanaka

History of Tomioka, Yashica and Carl Zeiss

Tomioka was a significant lens manufacturer – they made lenses for many companies, including Mamiya and Yashica. In 1968 Yashica purchased Tomioka, and it became a subsidiary. Then in 1972, Yashica and Carl Zeiss started cooperating. In 1983 Tomioka became a member of the Kyocera ceramic group following its takeover of Yashica.

Any claims stating that Carl Zeiss and Yashica / Tomioka collaborated on Sekor 55mm f1.4 because Carl Zeiss and Yashica / Tomioka were working together must be considered within the timeline of events.

There was no formal cooperation until 1972, so the Yashica / Carl Zeiss cooperation could not have impacted the release of the 55mm f1.4 a few years earlier.

Timeline of events:

1946 – Mamiya built the Setagaya factory in Tokyo to be self-sufficient in manufacturing shutters and lenses.

1959 – Contarex 55mm f1.4 patented by Johannes Berger and Guenther Lange (Carl Zeiss patent – DE1170157)

1961 – Carl Zeiss releases 55mm f1.4 for Contarex

1962 – Wakimoto Zenji files a patent for the 7-element lens design. Nikon releases Nikkor-S Auto 50mm f/1.4, using the Wakimoto formula.

1963 – Mamiya builds a new factory in Urawa City and starts operations.

1963 – Mamiya absorbed Setagaya Koki Co., Ltd. and transformed it into the Tokyo Factory.

1964 – Mamiya abolished the Tokyo factory, integrated it into the Urawa factory, and started outsourcing lens production to other manufacturers, including Tomioka.

1964 – Wakimoto Zenji and Simizu Yoshiyuki filed another patent in Japan for the design used in Nikkor-S Auto 50mm f/1.4. (No. 1964-87702)

1966 – The release of Mamiya 55mm f1.4 along with Mamiya 500TL / Auto Chinon Tomioka 55mm f1.4 by Tomioka.

1967 – Carl Zeiss Jena Pancolar 55mm f1.4 released

1968 – Yashica acquires Tomioka

1970 – Carl Zeiss stops production of Contarex 55mm f1.4 in Germany

1972 – Likely patent expiry date for Contarex 55mm f1.4

1972 – Zeiss lens production focuses mainly on Rollei SL 35, Contarex line wound down.

1972 – Carl Zeiss and Yashica launched a cooperative venture with the in-house name of “Top Secret Project 130.”

1972 May 4 – Olympus files patent for G.ZUIKO AUTO-S 50mm F1.4

1972 June 30 – Karl-Heinrich Behrens, Erhard Glatzel patent Zeiss Planar 50mm f1.4 (DE2232101A)

1973 – Zeiss Planar 50mm f 1.4 for Contax and Rollei SL 35 released

1975 – Rollei released Rolleinar AR 55mm f1.4 using the same optical design as Mamiya 55mm f1.4 from 1966

1977 – Mamiya introduces 50mm f1.4 CS for the NC1000 system with a ‘seven element / six group’ optical design.

1984 – Carl Zeiss finally granted a Japanese patent for a ‘seven element / six group’ Planar 50mm f1.4

1984 – Mamiya stops making 35mm cameras

Conclusion

Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 has a special place in my heart. I like it for its complex history, beautiful pictures, and quality engineering. I rate it 5 out of 5.

Some theories on the origins of the Mamiya Sekor 55mm f1.4 are more likely than others; however, without any hard evidence, it is impossible to know for sure who designed it. I lean towards the domestic Japanese origin – given the facts, it makes the most sense.

If you liked the review or have any further information which could improve it – please get in touch or leave a comment. Kindly thanks!

Sample photos

Leave a Reply